So, I Got Stabbed in Colombia

Editor’s Note: I wavered on writing about this for a long time since I didn’t want to put people off on Colombia or perpetuate the myth that danger lurks around every corner. As you can tell from my posts here, here, here, and here, I really love the country. I mean, it’s awesome. (And there will be plenty more blog posts about how great it is.) But I blog about all my experiences — good or bad — and this story is a good lesson on travel safety, the importance of always following local advice, and what happens when you stop doing so.

“Are you OK?”

“Here. Have a seat.”

“Do you need some water?”

A growing crowd had gathered around me, all offering help in one form or another.

“No, no, no, I think I’ll be OK,” I said, waving them off. “I’m just a little stunned.”

My arm and back throbbed while I tried to regain my composure. “I’m going to be really sore in the morning,” I thought.

“Come, come, come. We insist,” said one girl. She led me back onto the sidewalk, where a security guard gave me his chair. I sat down.

“What’s your name? Here’s some water. Is there anyone we can call?”

“I’ll be fine. I’ll be fine,” I kept replying.

My arm throbbed. “Getting punched sucks,” I said to myself.

Regaining my composure, I slowly took off the jacket I was wearing. I was too sore for any quick movements anyway. I needed to see how bad the bruises were.

As I did so, gasps arose from the crowd.

My left arm and shoulder were dripping with blood. My shirt was soaked through.

“Shit,” I said as I realized what had happened. “I think I just got stabbed.”

There’s a perception that Colombia is unsafe, that despite the heyday of the drug wars being over, danger lurks around most corners and you have to be really careful here.

It’s not a completely unwarranted perception. Petty crime is very common. The 52-year civil war killed 220,000 people — although thankfully there are drastically fewer casualties since the 2016 peace agreement.

While you are unlikely to be blown up, randomly shot, kidnapped, or ransomed by guerrillas, you are very likely to get pickpocketed or mugged. There were over 200,000 armed robberies in Colombia in 2018. While violent crimes have been on the decline, petty crime and robbery have been on the upswing.

Before I went to Colombia, I’d heard countless stories of petty theft. While there, I heard even more. A friend of mine had been robbed three times, the last instance at gunpoint while on his way to meet me for dinner. Locals and expats alike told me the same thing: the rumors of petty theft are true, but if you keep your wits about you, follow the rules, and don’t flash your valuables, you’ll be OK.

There’s even a local expression about it: “No dar papaya” (Don’t give papaya). Essentially, it means that you shouldn’t have something “sweet” out in the open (a phone, computer, watch, etc.) that would make you a target. Keep your valuables hidden, don’t wander around places you shouldn’t at night, don’t flash money around, avoid leaving nightlife spots alone, etc. Simply put: Don’t put yourself in a position where people can take advantage of you.

I heeded such advice. I didn’t wear headphones in public. I didn’t take my phone out unless I was in a group or a restaurant, or completely sure no one else was around. I took just enough money for the day with me when I left my hostel. I warned friends about wearing flashy jewelry or watches when they visited.

But the longer you are somewhere, the more complacent you get.

When you see locals on their phones in crowded areas, tourists toting thousand-dollar cameras, and kids wearing Airpods and Apple Watches, you begin to think, “OK, during the day, it’s not so bad.”

The more nothing happens to you, the more careless you get.

Suddenly, you step out of a café with your phone out without even thinking about it.

In your hands is papaya.

And someone wants to take it.

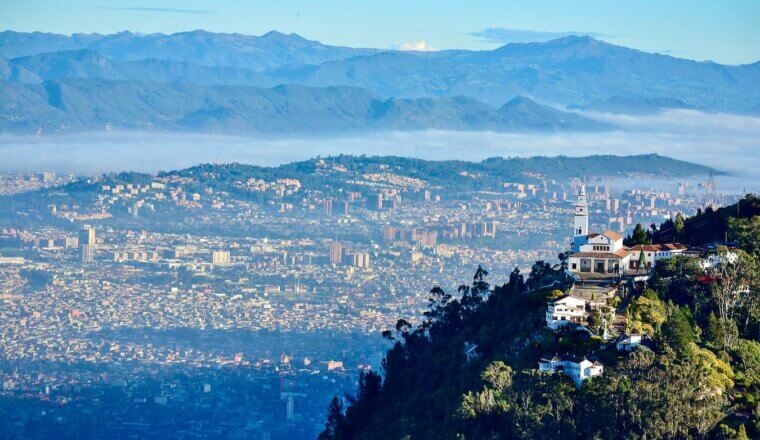

It was near sunset. I was on a busy street in La Candelaria, the main tourist area of Bogotá. The café I had been at was closing, so it was time to find somewhere new. I decided to head to a hostel to finish some work and take advantage of happy hour.

I’d been in Bogotá for a few days now, enjoying a city most people write off. There was a charm to it. Even in the tourist hot spot of La Candelaria, it didn’t feel as gringo-fied as Medellín. It felt the most authentic of all the big Colombian cities I had visited. I was loving it.

I exited the café with my phone out, finishing a text message. It had slipped my mind to put it away. It was still light outside, there were crowds around, and lots of security. After nearly six weeks in Colombia, I had grown complacent in situations like this.

“What’s really going to happen? I’ll be fine.”

Three steps out of the door, I felt someone brush up against me. At first, I thought it was someone running past me until I quickly realized that a guy was trying to take my phone out of my hand.

Fight or flight set in — and I fought.

“Get the fuck off me!” I shouted as I wrestled with him, keeping an iron grip on my phone. I tried pushing him away.

“Help, help, help!” I yelled into the air.

I distinctly remember the confused look on his face as if he had expected an easy mark. That the phone would slip out of my hand and he’d be gone before anyone could catch him.

Without a word, he started punching my left arm, and I continued to resist.

“Get off me! Help, help!”

We tussled in the street.

I kicked, I screamed, I blocked his punches.

The commotion caused people to run toward us.

Unable to dislodge the phone from my hand, the mugger turned and ran.

After people helped me sit down and the adrenaline wore off, I got light-headed. My ears rang. I had trouble focusing for a few moments.

Blood was dripping through my soaked shirt.

“Fuck,” I said looking at my arm and shoulder.

I tried to compose myself.

Having grown up surrounded by doctors and nurses, I ran through a quick “how bad is this” checklist in my mind.

I made a fist. I could feel my fingers. I could move my arm. “OK, I probably don’t have nerve or muscle damage.”

I could breathe and was not coughing up blood. “OK, I probably don’t have a punctured lung.”

I could still walk and feel my toes.

My light-headedness dissipated.

“OK, there’s probably not too much major damage,” I thought.

Words I didn’t understand were spoken in Spanish. A doctor arrived and helped clean and put pressure on my wounds. A young woman in the crowd who spoke English took my phone and voice-texted my only friend in Bogotá to let her know the situation.

As an ambulance would take too long, the police, who numbered about a dozen by now, loaded me onto the back of a truck and took me to a hospital, stopping traffic on the way like I was an honored dignitary.

Using Google Translate to communicate, the police checked me in at the hospital. They took down as much information as they could, showed me a picture of the attacker (yes, that’s him!), and called my friend to update her about where I was.

As I waited to be seen by the doctors, the owner of my hostel showed up. After having taken my address, the cops had phoned up the hostel to let them know what happened and she had rushed down.

The hospital staff saw to me quickly. (I suspect being a stabbed gringo got me quicker attention.)

We went into one of the exam rooms. My shirt came off, and they cleaned my arm and back and assessed the damage.

I had five wounds: two on my left arm, two on my shoulder, and one on my back, small cuts that broke the skin, with two looking like they reached the muscle. If the knife had been longer, I would have been in serious trouble: one cut was right on my collar and another especially close to my spine.

When you think of the term “stabbing,” you think of a long blade, a single deep cut into the abdomen or back. You picture someone with a protruding knife being rolled into the hospital on a stretcher.

That was not the case for me. I had been, more colloquially correct, knifed.

Badly knifed.

But just knifed.

There was no blade protruding from my gut or back. There would be no surgery. No deep lacerations.

The wounds wouldn’t require any more than antibiotics, stitches, and time to heal. A lot of time. (How much time? This happened at the end of January, and it took two months for the bruising to go down.)

I was stitched up, taken for an X-ray to make sure I didn’t have a punctured lung, and required to sit around for another six hours as they did a follow-up. My friend and hostel owner stayed a bit.

During that time, I booked a flight home. While my wounds weren’t severe and I could have stayed in Bogotá, I didn’t want to risk it. The hospital refused to give me antibiotics and, being a little suspicious of their stitching job, I wanted to get checked out back home while everything was still fresh. When I was leaving the hospital, I even had to ask them to cover my wounds — they were going to leave them exposed.

I figured it was better to be safe than sorry.

Looking back, would I have done anything differently?

It’s easy to say, “Why didn’t you just give him your phone?”

But it’s not as if he led with a weapon. Had he done so, I obviously would have surrendered the phone. This kid (and it turned out he was just about 17) just tried to grab it from my hand, and anyone’s natural instinct would be to pull back.

If someone tried to steal your purse, take your computer while you were using it, or grab your watch, your initial, primal reaction wouldn’t be, “Oh well!” It would be, “Hey, give me back my stuff!”

And if that stuff were still attached to your hand, you’d pull back, yell for help, and hope the mugger would go away. Especially when it’s still daytime and there are crowds around. You can’t always assume a mugger has a weapon.

Based on the information I had at the time, I don’t think I would have done anything differently. Instinct just set in.

Things could have been a lot worse: He could have had a gun. I could have turned the wrong way, and that small blade (so small in fact that I didn’t even feel it during the attack) could have hit a major artery or my neck. A longer blade might have caused me to recoil more and drop my phone. I don’t know. If he had been a better mugger, he would have kept running forward and I wouldn’t have been able to resist as the forward motion made the phone leave my hand.

The permutations are endless.

This was also just a matter of being unlucky. A wrong-time-and-wrong-place situation. This could have happened to me anywhere. You can be in the wrong place at the wrong time in a million places and in a million situations.

Life is risk. You’re not in control of what happens to you the second you walk out the door. You think you are. You think you have a handle on the situation — but then you walk out of a café and get knifed. You get in a car that crashes or a helicopter that goes down, eat food that hospitalizes you, or, despite your best health efforts, drop dead from a heart attack.

Anything can happen to you at any time.

We make plans as if we are in control.

But we’re not in control of anything.

All we can do is control our reaction and responses.

I really like Colombia. And I I really like Bogotá. I The food was delicious and the scenery breathtaking. Throughout my visit there, people were inquisitive, friendly, and happy.

And when this happened, I marveled at all the people who helped me, who stayed with me until the police came, the many police officers who assisted me in numerous ways, the doctors who attended to me, the hostel owner who became my translator, and my friend who drove an hour to be with me.

Everyone apologized. Everyone knew this was what Colombia is known for. They wanted to let me know this was not Colombia. I think they felt worse about the attack than I did.

But this experience reminded me of why you can’t get complacent about your safety. I gave papaya. I shouldn’t have had my phone out. When I left the café, I should have put it away. It didn’t matter the time of day. That’s the rule in Colombia. Keep your valuables hidden. Especially in Bogotá, which does have a higher rate of petty crime than elsewhere in the country. I didn’t follow the advice.

And I got unlucky because of it. I’d been having my phone out too often and, with each non-incident, I grew more and more relaxed. I kept lowering my guard more and more.

What happened was unlucky — but it didn’t need to happen if I had followed the rules.

This is why people always warned me to be careful.

Because you never know. You’re fine until you aren’t.

That said, you’re still unlikely to have a problem in Colombia. All those incidents I talked about? All involved people breaking the ironclad “no dar papaya” rule and either having something valuable out or walking alone late at night in areas they shouldn’t have. So don’t break the rule! (Of course, this could have happened anywhere in the world where I didn’t follow the safety rules that help minimize risk.)

But, also know, if you do get into trouble, Colombians will help you out. From my hostel owner to the cops to the people who sat with me when it happened to the random guy in the hospital who gave me chocolate, they made a harrowing experience a lot easier to deal with. It turns out that you can sometimes depend on the kindness of strangers.

I’m not going to let this freak incident change my view of such an amazing country. I’d go back to Colombia the same way I’d get in a car after an accident. In fact, I was terribly upset to leave. I was having an amazing time. I still love Bogotá. I still have plans to go back to Colombia. I have more positive things to write about it.

Learn from my mistake — not only for when you visit Colombia but when you travel in general.

You can’t get complacent. You can’t stop following the safety rules.

And still, go to Colombia!

I’ll see you there.

A couple of other points:

While the doctors were nice and the stitching turned out to be great, I wouldn’t go to a public hospital in Colombia again. That was not a fun experience. It wasn’t super clean, they had patients in the hallways, they didn’t give me antibiotics or pain medicine or cover my wounds, and they wanted to send me home without a shirt (thanks to my hostel owner for bringing me an extra!). There were just some basic things I was shocked they overlooked.

This is a strong case for travel insurance! I’ve always said that travel insurance is for unknowns, because the past is not prologue. In my twelve years of travel, I was never mugged — until I was. Then, needing medical care and a last-minute flight home, I was glad I had insurance. I needed it bad. It could have been a lot worse than a $70 hospital bill and a flight back home, too: if I had required surgery or had to be admitted to the hospital, that bill would have been a lot more. Don’t leave home without travel insurance. You never, ever know when you might need it, and you’ll be glad you had it!

Here are some articles on travel insurance:

- Why You Should Get Travel Insurance When You Travel

- How to Find the Best Insurance

- 13 Common Travel Insurance Questions Answered

They did catch the kid who tried to mug me. There’s security everywhere in Bogotá. He made it one block before they caught him. My hostel owner tells me he is still in jail. He was only 17. I feel bad for him. There’s a lot of poverty in Bogotá. There’s a very stark income divide there. Assuming he’s not some middle-class punk, I can understand the conditions that led him to rob me. I hope his future gets brighter.

Book Your Trip to Colombia: Logistical Tips and Tricks

Book Your Flight

Use Skyscanner to find a cheap flight. It is my favorite search engine because it searches websites and airlines around the globe, so you always know no stone is being left unturned.

Book Your Accommodation

You can book your hostel with Hostelworld as it has the biggest inventory and best deals. If you want to stay somewhere other than a hostel, use Booking.com, as it consistently returns the cheapest rates for guesthouses and hotels.

Don’t Forget Travel Insurance

Travel insurance will protect you against illness, injury, theft, and cancelations. It’s comprehensive protection in case anything goes wrong. I never go on a trip without it, as I’ve had to use it many times in the past. My favorite companies that offer the best service and value are:

- Safety Wing (for everyone below 70)

- Insure My Trip (for those 70 and over)

- Medjet (for additional repatriation coverage)

Looking for the Best Companies to Save Money With?

Check out my resource page for the best companies to use when you travel. I list all the ones I use to save money when I’m on the road. They will save you money too.

Want More Information on Colombia?

Be sure to visit our robust destination guide on Colombia for even more planning tips!